Mary Ann Gill, M.Ed., CCLS

Mary Ann Gill, M.Ed., CCLS is a child life specialist with experience in adaptive care, behavioral health, and hematology/oncology. She currently works as the program manager for SHINE, a clinical research program at Vanderbilt University Medical Center that offers medical, neurodevelopmental, and psychosocial care for infants and children who experienced prenatal opioid exposure.

.png?sfvrsn=ec177f4c_1)

A few times in my clinical practice, I have worked with children whose parents or caregivers have either a known or suspected diagnosis of intellectual disability (ID). While the skills of a Certified Child Life Specialist (CCLS) can easily translate to support for these families, some child life professionals may not feel adequately prepared to assess and address the psychosocial needs of parents/caregivers with ID. Personally, I entered the child life field with prior experience supporting adults with ID in an inclusive college program, but my knowledge of parents/caregivers with ID was still very limited. Through ongoing experience in the healthcare setting and staying up to date with relevant research, I have continued building my knowledge and skillset for working with this population. I am writing this article with the goals of educating fellow child life professionals and students about the strengths, needs, and experiences of parents/caregivers with ID and offering specific strategies for supporting these families.

A note on language: I have written articles about autism using mostly identity-first language (“autistic person” rather than “person with autism”), as a growing majority of autistic self-advocates, myself included, prefer identity-first language (Taboas et al., 2023). There is evidence of increased preference for identity-first language among disabled people overall (Sharif et al., 2022). However, this trend does not apply to every subset of people with disabilities. It’s difficult to find data on the language preferences of people with ID, who are often left out of research (Grech et al., 2024; Riches et al., 2020). My anecdotal experience suggests a more frequent preference for person-first language, so here I default to “person with ID.” In practice, it’s best to ask each individual what words they prefer to use for their disability. Most importantly, avoid the use of negative language and euphemisms. Note that “mental retardation” used to be the medical term for intellectual disability, but it was replaced because “the R-word" was so broadly adopted as a slur.

What is an intellectual disability?

.png?sfvrsn=6a177f4c_1)

The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual, 5th edition (DSM-5) defines an intellectual disability as a condition characterized by each of the following traits:

- deficits in intellectual functioning (e.g. reasoning, problem-solving, planning, abstract thinking), typically measured by an IQ score of less than 70

- deficits in adaptive functioning (e.g. communication, social participation, independent living skills) onset during childhood or adolescence

In the United States, intellectual disability is one of 13 disability categories that can qualify a child for special education services under the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA). English speakers in other countries might use different terms for this condition. British professionals, for example, use the term “learning disability.”

Can people with intellectual disabilities become parents?

Yes! Adults with ID are a diverse group with wide variation in strengths and support needs. Many people with ID report wanting to become parents (Guénoun et al., 2022). Sadly, the history of disabled people in the U.S. is marked by institutionalization and forced sterilization. Proponents of the eugenics movement worked to limit disabled people’s ability to reproduce (Grenon & Merrick, 2014). Today, people with ID are still at risk of institutionalization and forced sterilization, but support and recognition for parents/caregivers with ID is growing (Pérez-Curiel et al., 2023). At least 4.5 million parents in the United States have some form of disability (National Center for Research on Parents with Disabilities, 2024). People with ID, like those with other types of disabilities, can and do become effective parents.

The DSM-5 defines four categories of intellectual disability based on level of support needs. Most parents/caregivers with ID would be considered to fall in the “mild” range (Llewellyn & Hindmarsh, 2015). However, parental IQ itself does not predict child wellbeing. Instead, the mental health and social support of parents with ID predict child developmental outcomes (Llewellyn & Hindmarsh, 2015). Interventions designed to improve parents’ psychosocial wellbeing may help improve child outcomes (Crnic et al., 2017).

Still, parents/caregivers with ID and their children face unique challenges, including a higher risk of complications with pregnancy and birth and higher rates of developmental delay in children (Akobirshoev et al., 2017; Llewellyn & Hindmarsh, 2015). Socioeconomic status could play a primary role in these correlations, as people with ID are more likely to live in poverty (Powell & Parish, 2016). Parents/caregivers with ID also experience disproportionate interactions with the child protection system. Research suggests that parents with ID are equally as likely as parents without ID to have child abuse or neglect cases (Slayter & Jensen, 2019), but parents with ID are much more likely to experience child removal and custody loss (LaLiberte et al., 2016; Llewellyn & Hindmarsh, 2015; Sigurjónsdóttir & Rice, 2018).

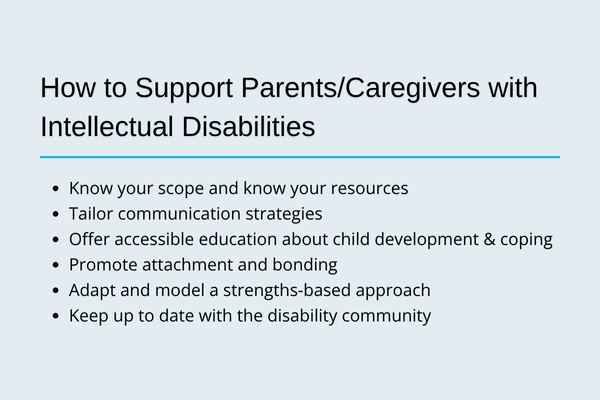

How can we better support parents/caregivers with intellectual disabilities

Know your scope and know your resource

When supporting parents/caregivers with ID as part of a multidisciplinary team, it’s important to stay within your scope of practice. I once received a consult to create a daily schedule for a hospitalized infant. The bedside nurse wanted a visual support to offer the infant’s parents as they learned to administer her medications several times per day. Before responding, I talked with my supervisor about my role and scope in this process. We agreed that I could create a daily schedule incorporating developmentally appropriate routines and playtime, but I would not include any information about the infant’s medication, including type, timing, and dosage, as that type of education should fall to the nursing team.

When you do assess needs outside your scope of practice, it’s always helpful to know what other resources are available. If your hospital has a patient education department, members of that team may offer specialized support for staff and providers navigating unique health literacy needs. A hospital social worker may be aware of community resources that could benefit the family. For example, my social work colleague recently made a referral to an evidence-based home visiting program to help a mother with ID access additional parenting support.

Tailor communication strategies

During conversations with parents/caregivers with ID, speak in short sentences, use concrete and simple language, and allow extra time for processing. You can repeat any important points multiple times, rephrasing as needed. Try to keep questions open-ended rather than leading or guiding, as people with ID may be more likely to acquiesce (respond with a “yes’) to questions they do not understand (Finlay & Lyons, 2002). Use teachback strategies to ensure understanding: ask the parent/caregiver to repeat back what you told them in their own words.

Even for non-disabled people, communication abilities can fluctuate during a stressful situation. These communication strategies can be helpful to use with any parent/caregiver. Remember that using the above communication strategies does not mean that you should use “baby talk.” Disabled adults are adults and do not want to be treated like children.

Offer accessible education about child development and coping

Offer accessible education about child development and coping

Many interventions for parents/caregivers with ID involve education about child development (Coren et al., 2010; Glazemakers & Deboutte, 2012), which CCLSs are uniquely equipped to provide. You might educate parents/caregivers about using play to encourage developmental progress, or you might provide information about how children at various developmental stages typically respond to stressful events and suggest ways to improve their coping.

When educating parents/caregivers, pay attention to accessibility. Use a mixture of teaching methods, such as verbal information, written information, pictures/videos, and modeling. For written materials, you can use a readability calculator to check the reading grade level of the text. Also, make sure that any activities you provide or suggest to a family are accessible to the parent/caregiver. A parent/caregiver who struggles with reading comprehension may not feel comfortable reading a book aloud to their child, but they might enjoy playing through a look-and-find book or listening to an audiobook together.

The parents of the hospitalized infant I mentioned earlier asked me for help decorating her room. After providing some themed decorations for normalization, I also designed a colorful poster listing ways to play with a newborn. I included pictures and used a readability calculator to edit the text to around a fourth grade reading level. The poster fit right into the room decor and gave the parents an easy reference to remember the play strategies we were working on.

Promote attachment and bonding

As we do for other families, CCLSs can work to promote healthy attachment and bonding between children and parents/caregivers with ID. Help the parent/caregiver identify ways to participate in their child’s care. Teach parents/caregivers positive ways to engage with their children regardless of medical status. Support families as they make memories together.

I worked with a mother to create a baby book capturing photos and stories about her hospitalized child. When a DCS referral was placed and the possibility of a foster placement arose, we started a second book that could travel with the child if needed. This provided an extra point of connection for the mother and child and helped inspire friendly communication between the biological and foster families. Since parents/caregivers with ID are more likely to interact with the child protection system, these types of interventions can be particularly valuable.

Adapt and model a strengths-based approach

While it's important to anticipate the challenges that parents/caregivers ID may face, we should also recognize and celebrate each family’s unique strengths. Focus on what the parent/caregiver can do, not just the things that are hard for them. Ask questions to understand the family’s values and goals. Healthcare professionals may be quick to make negative assumptions about parents/caregivers with ID. You can help combat this by getting to know parents/caregivers and pointing out their strengths during conversations with the multidisciplinary team.

Keep up to date with the disability community

The disability community evolves quickly. Language preferences are always changing, and political events can have huge impact on the day-to-day activities and wellbeing of disabled people. As I’m writing this, many of my disabled friends, patients, and colleagues in the U.S. fear losing access to crucial medical care. Staying on top of current events impacting people with ID can improve your ability to assess the psychosocial needs of parents/caregivers.

Local disability-related organizations might help you stay up to date on political events. My state's Council onDevelopmental Disabilities sends out a monthly electronic newsletter that includes information on public policy changes relevant to people with intellectual and developmental disabilities. I also recommend seeking opportunities to hear directly from disabled self-advocates, including through social media. People with ID are often left out of research, but social media can be a powerful tool for people with ID to make their voices heard.

Conclusion & Resources for Ongoing Learning

People with ID face numerous barriers to parenthood, including negative attitudes from relatives and caregivers, lack of knowledge from healthcare professionals, and the ongoing practice of forced sterilization (Pérez-Curiel et al., 2023). Still, “people with intellectual disability have always become parents” (Llewellyn & Hindmarsh, 2015, pg 119). At least on occasion, child life specialists are likely to encounter parents and caregivers with ID. By working as a member of the multidisciplinary team to offer individualized, accessible support and resources for these families, CCLSs can optimize outcomes for children and caregivers alike. Those in the academic world should consider talking with child life students about ways to support parents/caregivers with all kinds of disabilities, including ID.

Below I have included a list of additional resources I found while working on this article. I hope that these serve as a helpful starting point to child life students and professionals wanting to improve their support for parents/caregivers with ID and their children.

- The Arc’s position statement on parents with intellectual and/or developmental disabilities

- Resources from the National Research Center for Parents with Disabilities at Brandeis University:

- Talking to people with disabilities who are parents or want to become parents: A guide for helpers

- Being good parents: A guide for parents with intellectual disabilities

- Advice for professionals working with parents with intellectual disabilities

- Advice and facts for mothers and expecting mothers with intellectual disabilities

_______________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

References

Akobirshoev, I., Parish, S. L., Mitra, M., & Rosenthal, E. (2017). Birth outcomes among US women with intellectual and developmental disabilities. Disability and Health, 10(3), 406-412.

American Psychiatric Association. (2022). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed., text rev.). https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.books.9780890425787

Coren, E., Hutchfield, J., Thomae, M., & Gustafsson, C. (2010). Parent training support for intellectually disabled parents. Campbell Systematic Reviews, 6(1), 1-60.

Crnic, K. A., Neece, C. L., McIntyre, L. L., Blacher, J., & Baker, B. L. (2017). Intellectual disability and developmental risk: Promoting intervention to improve child and family well-being. Child Development, 88(2), 436-445.

Finlay, W. M. L., & Lyons, E. (2002). Acquiescence in interviews with people who have mental retardation. Mental Retardation [now Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities], 40(1), 14-29.

Glazemakers, I., & Deboutte, D. (2012). Modifying the ‘Positive Parenting Program’ for parents with intellectual disabilities. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 57(7), 616-626.

Grech, L. B., Koller, D., & Olley, A. (2024). Person-first and identity-first disability language: Informing client centred care. Social Science & Medicine, 362, 117444.

Grenon, I., & Merrick, J. (2014). Intellectual and developmental disabilities: Eugenics. Frontiers in Public Health, 2, 201.

Guénoun, T., Essadek, A., Clesse, C., Mauran-Mignorat, M., Veyron-Lacroix, E., Ciccone, A., & Smaniotto, B. (2022). The desire for parenthood among individuals with intellectual disabilities: systematic review. Journal of Intellectual Disabilities, 29(2), 423-446.

Individuals with Disabilities Education Act, 33 U.S.C. §1401.

LaLiberte, T., Piescher, K., Mickelson, N., & Lee, M. H. (2017). Child protection services and parents with intellectual and developmental disabilities. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disability, 30(3), 521-532.

Llewellyn, G., & Hindmarsh, G. (2015). Parents with intellectual disability in a population context. Current Developmental Disorders Reports, 2, 119–126.

National Center for Parents with Disabilities. (2024). Who are disabled parents? [Data dashboard]. The Lurie Institute for Disability Policy. https://heller.brandeis.edu/parents-with-disabilities/who-are-disabled-parents.html

Pérez-Curiel, P., Vicente, E., Lucía Morán, M., & Gómez, L. E. (2023). The right to sexuality, reproductive health, and found a family for people with intellectual disability: A systematic review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20, 1587.

Powell, R. M., & Parish, S. L. (2016). Behavioural and cognitive outcomes in young children of mothers with intellectual impairments. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 61(1), 50-61.

Riches, T. N., O’Brien, P. M., & The CDS Inclusive Research Network. (2020). Can we publish inclusive research inclusively? Researchers with intellectual disabilities interview authors of inclusive studies. British Journal of Learning Disabilities, 48(4), 272-280.

Sigurjónsdóttir, H. B., & Rice, J. G. (2018). ‘Evidence’ of neglect as a form of structural violence: Parents with intellectual disabilities and custody deprivation. Social Inclusion, 6(2), 66-73.

Slayter, E. M., & Jensen, J. (2019). Parents with intellectual disabilities in the child protection system. Children and Youth Services Review, 98, 297-304.

Taboas, A., Doepke, K., & Zimmerman, C. (2023). Preference for identity-first versus person-first language in a US sample of autism stakeholders. Autism, 27(2), 565-570.