Kathryn Cantrell, PhD, CCLS

Assistant Professor, Texas Woman’s University

Mashal Kara, MS, MAT, CCLS

Professor, Texas Woman’s University

Child life is a young yet growing profession. In April 2020, we learned in the CCLS Connection that there are currently 6,170 certified child life specialists across the globe (ACLP communication, 2020). Though we are growing, when you compare that number to the number of people in other health care professions, it is easy to see why our friends in health care may still be unaware of our skill-set. There are over 251 nursing journals backing up the practice of 2.86 million registered nurses in the United States alone (Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2020). We do not have the affordance of those numbers. In order to contribute to conversations in health care research, our small profession must be heard amongst the voices of giants.

Recently, Sisk & Cantrell (2021) returned to Thayer’s (2007) question, “Is child life an emerging field of inquiry?” Authors concluded that while we are certainly developing a stand-alone academic discipline that regularly produces new knowledge through research, aka a field of inquiry, we are not there yet. Currently we are still a profession building an evidence base that will one day stand alone and support the growth of more academic pursuits. Certified Child Life Specialists have contributed to a body of child life research and scholarship that is growing into a field of inquiry. These contributions include textbook chapters, conference presentations, and publications in journals across the health care community. However, much of this work is difficult for the general public to access, limiting our ability to reach members of the health care community outside of the child life silo. Prior to 2021, peer-reviewed publications by the Association of Child Life Professionals (ACLP) (Child Life Focus and The Journal of Child Life: Psychosocial Theory and Practice) were behind the association’s paywall. Now that The Journal of Child Life is open access and it is easier to search for child life scholarship, we are in a critical period to produce research.

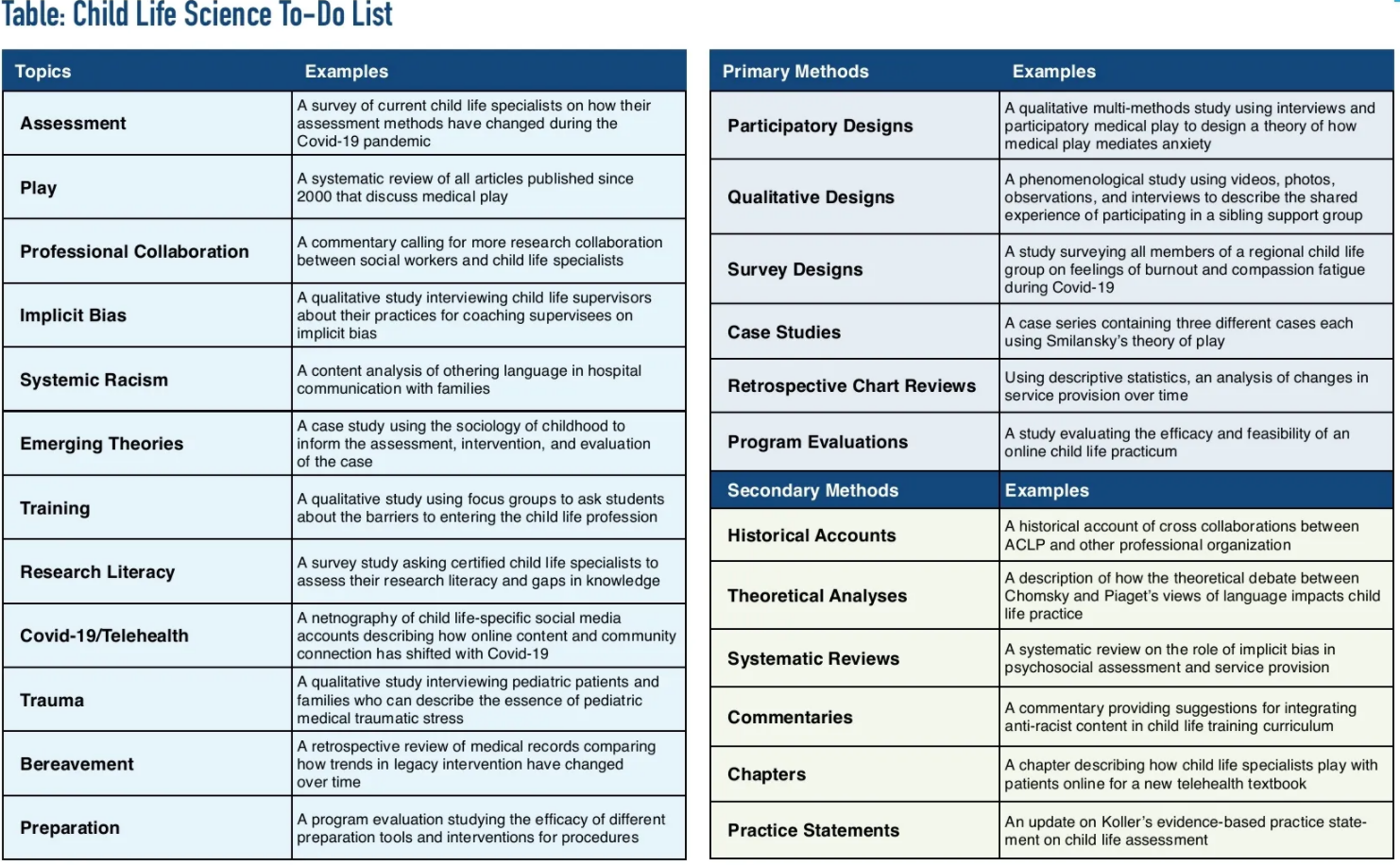

In addition to increasing access to our emerging field, it is essential to set ourselves apart from other psychosocial researchers and scholars. Our field of inquiry supports three components: the profession, the professional organization, and the academic discipline (Daniels & Sisk, 2021; Sisk & Cantrell, 2021). The more discrete and specific our field is, the more others will see our name and immediately know that we focus on the psychosocial needs of children and families in health care settings. This clarity can lead to job creation, more opportunities for ACLP, and growth in academic programs. In this paper, we propose an agenda for the emerging field of child life. By carefully tending the scientific conversations we engage in as a community, we can establish a field of inquiry more efficiently. This agenda is broken down in two sections, recommendations for primary and secondary research. In each section, we consider how to advocate for the profession while conducting valuable research and provide suggestions for content, methods, and dissemination. The paper concludes with a list of suggested studies for child life scientists (Table 1) and a request for more ideas.

Primary Research

In this paper we define child life scientists as any child life professional who contributes to evidence-based practice by disseminating their ideas for improving child life practice. While the term scientist may elicit the traditional image of someone in a lab coat hovered over a microscope, we want to be clear that science in child life does not adhere to this traditional view. Due to the profession’s youth, our science looks more deconstructed and can include anything from a description of an intervention to a systematic literature review to a randomized controlled trial. In this paper, we draw from recent child life publications to consider ways child life scientists can contribute to primary and secondary research, two possible ways to categorize science and organize the profession’s agenda. Primary research is the active work of collecting raw data and making practice suggestions based on the analyzed outcomes. Primary research can be analytical and draw practice conclusions such as a study evaluating the efficacy of an intervention. It can also be descriptive and provide insight into a current professional issue such as a study surveying child life specialists on their preferred assessment method. Conducting primary research is a form of advocacy. Primary research provides the data to back up our clinical decisions and acts as the foundation of evidence-based practice. Engaging in primary research communicates to the health care community that we have evolved past an applied profession relying on anecdotal evidence for decision-making.

While there are an endless number of psychosocial topics to explore with primary research, we suggest prioritizing assessment, play, and professional collaboration. Prioritizing these three topics for primary research will build a foundation to further solidify and define our scope of practice. In their content analysis of articles published in Child Life Focus, Turner and Boles (2020) note only 6.1% of papers published in Focus looked at Assessment, a domain that makes up 40% of the child life certification exam. Child life scientists might consider primary projects that further describe child life specialists’ unique approach to assessment such as survey designs, interviews, focus groups, observations, and case studies. Boles et al. (2021) conducted a scoping systematic review of all child life literature published between 1996 to 2017 and found only 7% of articles explored play. Of note, play content decreased between 2010-2017 as the percentage of content related to preparation and procedural support increased. Considering play is foundational to child life practice, child life scientists might consider a return to exploring play with primary research. Play, a broad concept in child life, can be explored with primary research in many different ways. For example, child life scientists may examine medical play and therapeutic play and how it relates to coping with hospitalization. Participatory research methods discussed later in this paper are ideal for studying play and showcasing the scope of child life practice. Authors also note the gap in articles looking at professional collaboration. Hasenfuss & Franceschi (2003) describe a case study of successful professional collaboration between a nurse and a child life specialist. However, there are few to none recent primary research studies that support the facilitation of professional collaboration including collaboration with members of the interdisciplinary team, an essential aspect of child life practice. A primary research study on barriers and facilitators of professional collaboration during a pandemic would help the profession know how to foster relationships during a shared trauma.

In addition to topics that clarify our scope, it is essential to engage in timely primary research. As a response to the profession’s published commitment to Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion (DEI) (ACLP, 2020), studies examining systemic racism in child life training can help us identify areas for improvement. Similarly, studies examining the role of implicit bias in child life assessment can help white child life specialists reflect on their practice. According to the 2018 ACLP Member Survey, 91% of respondents identified as Caucasian (ACLP, 2018). Child life specialists support diverse populations, and studies that inform training related to how child life specialists can self-evaluate and work toward increasing their cultural humility is crucial. Part of child life practice is advocacy, including advocating for equitable health care for all patients and families. Primary research studies will equip child life specialists with tools and strategies on how to carry out this role. In addition to DEI, child life researchers can investigate training to support the marked growth of the profession. Studies examining child life pedagogy, intern selection practices, and preparation for the certification exam can lead to more equitable and efficient training. Lastly, in the past decade we have seen an increase in the integration of a trauma-informed lens in child life practice that is especially timely during the Covid-19 pandemic. Conducting primary research on child life assessment and intervention practices that seek to decrease trauma symptoms would be a crucial next step to the conversation already started by Shea et al. (2021) in Pediatric Medical Traumatic Stress, published in the March issue of JCL. As previously mentioned, JCL is now searchable and open-access, allowing for more readers of child life inquiry. Now is the time to evaluate our research literacy and create more professional development opportunities for strengthening research competence. Primary research can help investigate our current knowledge and skills and evaluate our academic preparation. Lastly, primary research on the impact of Covid-19 and telehealth practices would help us prepare for future pandemics.

Regarding suggestions for primary research methods, we return to the work of Boles et al. (2021) who, in their scoping review, found a trend toward quantitative methods in child life articles published since 2010. In an effort to reinforce the efficacy of our work in the setting of medicine, we have focused our attention on interventions that can be assessed from a medical approach. This narrowed vision has provided us with more credibility in health care but has derailed our scientific narrative away from some of the core values of our profession, including play. The decisions made when designing methods are also opportunities to clarify our work. Choosing methods that exemplify our strengths in building relationships, play, and making meaning, can set us apart from others in health care and reinforce a methodological niche that others are unable to fill. Participatory qualitative research that includes visual art techniques, medical play, games, puppets, storytelling, and writing as methods for data collection are a rich way to set us apart in health care research (Rollins, 2018; Sisk & Baker, 2019). Case studies that showcase our ability to integrate theory into practice are helpful learning tools for the many students entering the profession. Lastly, ethnographic methods such as autoethnography and netnography can be a way to flex child life competencies such as reflexivity and relationship building.

Writing up primary research is a time to advocate for the profession. The child life field of inquiry can support the practice of other professionals and sharing our work in nursing, medical, social work, or psychology journals might spark readers’ motivation to collaborate with child life. Boles et al. (2021) note a decrease in the number of articles being published in nursing, child health and development, psychology, music therapy, and family sciences; as of 2010, medical journals were the dominant outlet for child life research outside of ACLP publications. While this trend serves “to increase the recognizability of child life services to an audience most likely involved in health care administration and decision-making,” publishing in other discipline’s journals reinforces that child life is still a profession, rather than a field of inquiry that can sustain its own network of journals (Boles et al., 2021, p. 12). Child life scientists could consider a) contributing to child life’s growing field of inquiry by publishing in child life specific publications and b) publishing in interdisciplinary journals, educating readers about child life’s scope.

Additionally, authorship, author order, and title selection are other opportunities to support the growth of our field of inquiry. Turner and Boles (2020) note that most of the primary research articles published in Child Life Focus were first authored by non-Certified Child Life Specialists. Assigning child life specialists as first authors on primary research signals to other professions that we can support our own inquiry. Too, as child life scientists engage in more investigation of constructs central to DEI, it is essential to include authors from the underrepresented groups being studied. Ideally, the research team conducting the study would be representative of the racial and ethnic background of the participating sample. Lastly, choosing a title that includes the term “child life” and specifying “child life” as a keyword in your study can expedite our path to being a field of inquiry. These small details can result in it being easier for researchers to locate child life literature, leading to more citations and opportunities for collaboration.

Secondary Research

Secondary research is the process of making meaning from primary sources. Secondary research synthesizes, summarizes, and analyzes primary research to help professionals integrate evidence into their work. Without secondary research, a parallel commentary on the results of the primary studies would not occur, making it more difficult to access scientific conclusions. Secondary research helps create evidence-based practices and recommendations. Secondary research can include meta-analyses or systematic reviews whereby studies are summarized and practice recommendations are clarified. It can also include analyses of theoretical perspectives or historical trends in the profession. Secondary research is also a form of advocacy, especially since it is centered on promoting more access and dialogue. This paper is an example of secondary research.

There are an endless number of topics to explore with secondary research; yet, there are a handful that are more pressing than others. As previously mentioned, Tuner and Boles (2020) note the lack of papers exploring assessment published in Child Life Focus. This trend has continued in the articles published in JCL since its 2020 inception, making assessment a topic that is ready for exploration. Secondary projects such as reviews of assessment practices, updated evidence-based practice statements, and theoretical analyses would strengthen this domain. In addition, secondary projects providing professional education on anti-racism would reinforce ACLP’s commitment to DEI. Writing about specific ways to bring an anti-racist lens to assessment, intervention, and evaluation could be a valuable series for the community. Another topic that is important to consider for secondary research is compassion fatigue and burnout. Hoelscher & Ravert (2021) conducted a survey to understand burnout among CCLS and found that CCLS experience burnout related to workload, emotional burden, and poor work-life balance. More specifically, Burns-Nader et al. (2021) surveyed child life specialists supporting Pediatric-Sexual Assault Forensic Examinations and found that these child life specialists struggle with hearing the stories of the patients’ experiences. Secondary projects that review primary research related to burnout and compassion fatigue and provide recommendations would help training programs and workplaces to support CCLS in preventing burnout and compassion fatigue. Unlike assessment, play, and collaboration, legacy is a domain within child life where we see a promising number of child life publications. Still, there are needs for updates such as a reflection on how telehealth and Covid-19 have impacted our evolving definition of legacy building (Boles, 2014) and legacy building practices (Sick et al., 2012). Lastly, secondary projects updating the community on modern theoretical perspectives would ensure we are keeping up with the trends in developmental science. Commentaries reflecting on the practice implications of Koller (2019) and Koller and Wheelwright (2020) could result in more conversations about modernizing our theoretical repertoire.

If these topics do not lead to ideas, responding to the outcomes of primary research, especially when gaps are discussed, can lead to more dialogue. For example, Lookabaugh and Ballard (2018) surveyed practicing child life specialists about their perceived level of competence and found gaps in two areas: academic preparation and working with diverse families. Addressing gaps identified in survey research can be a helpful outcome of secondary research and continues a thread of dialogue. Regarding academic preparation, participants in Lookabaugh and Ballard (2018) noted a specific gap in knowledge about death and dying. A targeted secondary response to this paper could be a critical review of a new death and dying textbook, assessing its usefulness for practicing child life specialists or recommending its inclusion in bereavement courses. To address respondent’s noted gap in working with diverse families, a chapter on using critical race theory in child life practice could be a helpful addition to syllabi in child life academic programs. Responding to gaps noted in recent literature can help ensure your projects are making timely contributions to shared knowledge.

Methodological choices in secondary research can also support the profession’s growth. Child life specialists are naturally skilled at marking growth, using theory, and teaching. We can use our skills in marking and celebrating growth to maintain a detailed historical account of how the profession has changed and adapted over time. For example, a content analysis of meeting minutes from the ACLP Board of Directors could account for trends in community concerns. Historical accounts of our evolution in theory, scope of practice, assessment methods, and practice considerations will catalogue our growth and allow for reflection opportunities to challenge the status quo. We can showcase our skills in theoretical integration by writing theoretical analyses that are detailed and lead to specific practice recommendations. Lastly, child life scientists can embrace their skills in teaching to construct useful systematic reviews. The most meaningful reviews are the ones that can break down a complex topic of research into smaller, more accessible pieces.

Writing secondary research is advocating for child life and is another opportunity to teach about the profession. Secondary research is needed in child life specific publications like JCL and interdisciplinary journals. Papers like those cited in this commentary can help the child life community harness motivation for long-term goals like building a field of inquiry. These pieces can also be useful outside of the community. For example, a commentary calling for research collaboration that provides specific suggestions could be a great addition to a nursing or psychology journal. When mentoring emerging child life scientists, supporting secondary research skills is essential, especially from a social justice lens. Secondary research is faster than most primary methods, is lower-cost, and can be completed without institutional affiliation. Strengthening students’ skills in secondary research provides them with tools to contribute to child life science even if, say, a global pandemic derails their employment timeline.

Conclusion

Developmentally, our young profession is growing and our evidence-base is emerging into a new field of inquiry. As we work to nurture this new growth, contributing to both primary and secondary research can help child life scientists communicate in a room of larger, more established professions. Scientists should consider exploring topics such as assessment, play, professional collaboration, DEI, training preparation, and the impact of Covid-19. Likewise, choosing methods that exemplify our scope of practice and professional strengths further advocates for our unique approach. Qualitative and participatory methods enable child life scientists to be creative in their research whereas secondary projects like systematic literature reviews and theoretical analyses showcase our skills in teaching. Lastly, the choices we make during dissemination can contribute to the field’s growth. As such, including child life specialists as authors, publishing both inside and outside of the child life community, ensuring authorship is representative of the sample, and including “child life” in the title or keywords are each forms of advocacy.

Primary research paves a path for secondary projects that provide strong, credible conclusions and recommendations. This paper’s discussion of secondary research is intentional. Shared knowledge will always be more truthful than the knowledge of a single, isolated child life specialist. As we quickly construct a field of inquiry that can sustain our profession, ACLP, and our academic programs, we must communicate across these three concentrations or we risk duplicating work. Scholarly dialogue facilitates this process and provides a record of our evolving ideas. Too, the more we talk, the more citations that include the words “child life” enter the either. So to conclude, we end with a prompt for more secondary dialogue: What do you see as the greatest research priority for our emerging field? What suggestions do you have for fellow child life professionals looking to contribute?

REFERENCES:

Association of Child Life Professional (2018). 2018 ACLP member survey. https://www.childlife.org/docs/default-source/default-document-library/aclp-2018-year-in-review.pdf?sfvrsn=454cb24d_4

Boles, J., Turner, J., Rights, J., & Lu, R. (2021). Empirical evolution of child life. The Journal of Child Life: Psychosocial Theory and Practice, 2(1), 4-14.

Boles, J. (2014). Creating a legacy for and with hospitalized children. Pediatric Nursing, 40(1), 43.

Hasenfuss, E. & Franceschi, A. (2003). Collaboration of nursing and child life: A palette of professional practice. Journal of Pediatric Nursing, 18(5), 359-365.

Hoelscher, L., & Ravert, R. (2021). Workplace relationships and professional burnout among certified child life specialists. The Journal of Child Life: Psychosocial Theory and Practice, 2(1), 15-25.

Lookabaugh, S., & Ballard, S. M. (2018). The scope and future direction of child life. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 27(6), 1721-1731.

Koller, D. (2019). New ways of thinking and doing: A theoretical vision for child life. Child Life Bulletin, 37(4), 10-14.

Koller, D. & Wheelwright, D. (2020). Disrupting the status quo: A theoretical vision for the child life profession. The Journal of Child Life: Psychosocial Theory and Practice, 1(2), 27-32.

Rollins, J. (2018). Being participatory through play. In Being Participatory: Researching with Children and Young People (pp. 79-102). Springer, Cham.

Schmitz, A., Burns-Nader, S., Berryhill, B., & Parker, J. (2021). Supporting children experiencing a Pediatric-Sexual Assault Forensic Examination: Preparation for and perceptions of the role of the child life specialist. The Journal of Child Life: Psychosocial Theory and Practice, 2(1), 55-66.

Sisk, C. & Baker, J. (2019). Medical play: From intervention to participatory research. In Participatory Methodologies to Elevate Children’s Voice and Agency (pp. x-x). Information Age Publishing, Inc: Charlotte, NC.

Sisk, C. & Cantrell, K. (2021). How far have we come? ACLP Bulletin, 39(2), 24-30.

Sisk, C., Walker, E., Gardner, C., Mandrell, B., & Grissom, S. (2012). Building a legacy for children and adolescents with chronic dis- ease. Journal of Pediatric Nursing, 27(6), e71-e76.

Shea, T., Athanasakos, E., Cleeve, S., Croft, N., & Gibbs, D. (2021) Pediatric medical traumatic stress. The Journal of Child Life: Psychosocial Theory and Practice, 2(1), 42-54.

Turner, J., & Boles, J. (2020). A content analysis of professional literature in Child Life Focus: 1999-2019. The Journal of Child Life: Psychosocial Theory and Practice, 1(1), 15-24.